The Role of Year-Round Strength and Conditioning in Athlete Development

In pursuing peak athletic performance, year-round strength and conditioning (S&C) isn't just an option—it's a necessity. The continuous application of scientifically grounded training principles is key to developing resilient, high-performing athletes. This article explores the critical importance of uninterrupted S&C, diving deep into the science behind why this approach is essential for long-term athlete development.

The Science of Continuous Adaptation

Physiological Adaptation

In exercise science, adaptation refers to the body's physiological changes in response to stress, such as training. These changes include muscle size (hypertrophy), cardiovascular efficiency improvements, and neuromuscular coordination. Continuous adaptation is crucial because the body will only improve if consistently challenged.

Principle of Progressive Overload

This foundational concept in S&C dictates that for the body to continue adapting, it must be exposed to progressively greater levels of stress. This can mean increasing the weight lifted, the repetitions of a sprint, or the volume of training. Without the consistent, year-round application of progressive overload, athletes risk stagnation, where performance improvements halt or regress.

For example, an athlete might start a training cycle by squatting 200 pounds for 5 repetitions. Over weeks and months, by strategically manipulating acute training variables, such as the repetitions, load, or volume, the athlete may eventually squat 250 pounds for the same repetitions, demonstrating a positive adaptation.

However, this continuous progression can be disrupted by prolonged breaks, leading to detraining—a rapid loss of adaptations. Mujika and Padilla (2000) highlighted that endurance and strength decline significantly within just a few weeks of inactivity, underscoring the importance of a consistent training stimulus.

Periodization: A Strategic Approach

Periodization is the systematic planning of physical training. Its goal is to peak an athlete's performance for a specific time while preventing overtraining and burnout. This method divides the training year into macrocycles (yearly), mesocycles (monthly), and microcycles (weekly or daily).

Macrocycle: This is the entire training period, usually a year, which includes all phases of training—preparatory, competitive, and transition.

Mesocycle: Typically lasting several weeks to a few months, mesocycles focus on specific goals such as hypertrophy, strength, or power.

Microcycle: These are short, weekly or daily periods that dictate the training specifics for individual sessions.

Example: In a sport like football, the preparatory phase might focus on building general strength and conditioning, while the competitive phase hones sport-specific power and speed. The transition phase allows for recovery and psychological refreshment before the cycle repeats.

Issurin (2008) demonstrated that periodized training could lead to better performance gains than non-periodized or randomly structured programs. The periodization approach also helps manage the risk of overtraining, a condition characterized by decreased performance, increased injury risk, and psychological burnout.

Injury Prevention Through Strength Training

Injury Prevention

One of the most compelling reasons for year-round S&C is its role in injury prevention. Strength training increases muscle cross-sectional area, improves tendon stiffness, and enhances joint stability—factors that collectively reduce the likelihood of injury.

Muscle Imbalances and Injury

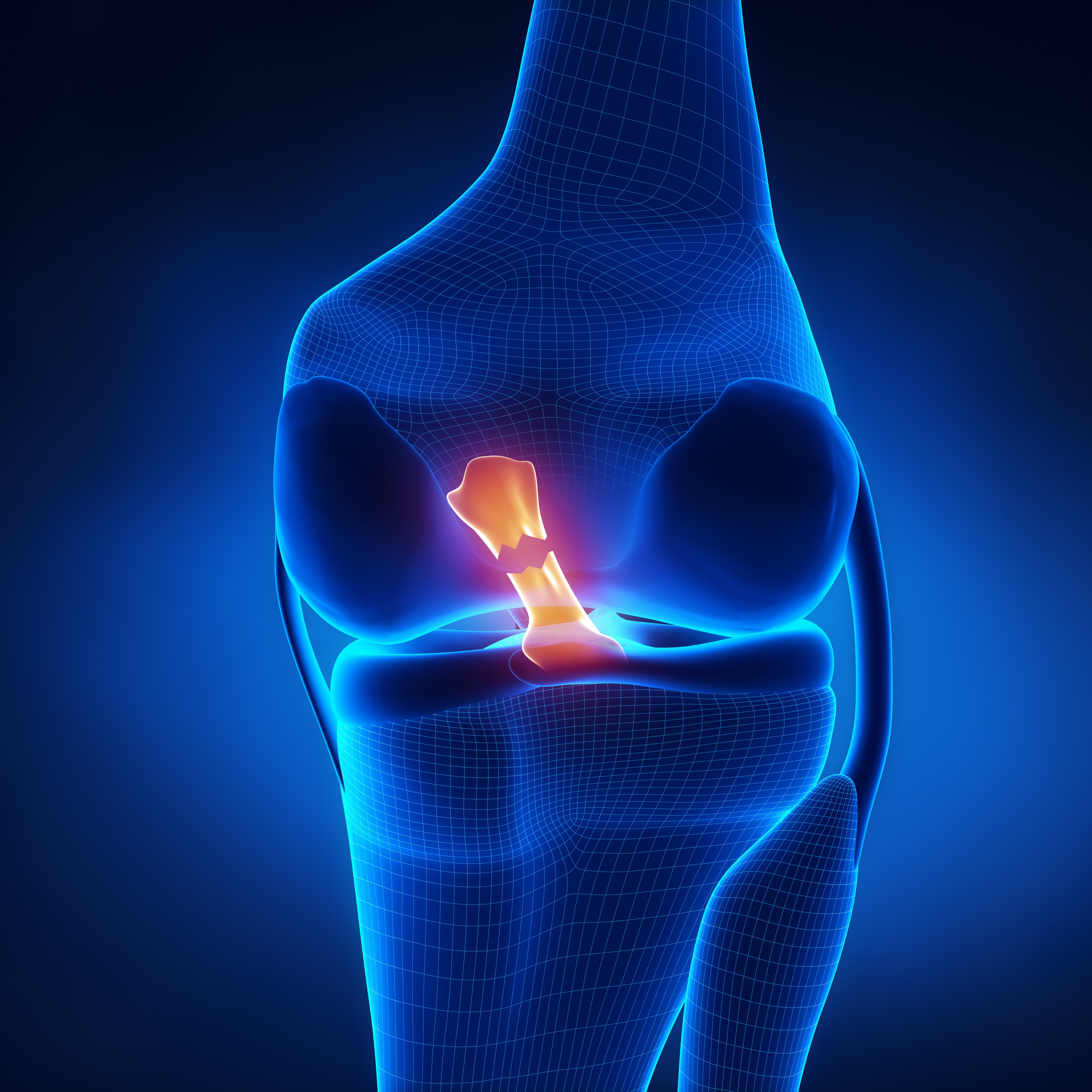

Many injuries stem from muscle imbalances, where one muscle group is significantly stronger or more flexible than its opposing group. For example, weak hamstrings relative to strong quadriceps can increase the risk of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries. Regular, balanced strength training addresses these imbalances by targeting both agonist (primary movers) and antagonist (opposing) muscle groups.

Lauersen et al. (2014) conducted a meta-analysis showing that strength training could reduce sports injuries by up to 68%. This finding illustrates that injury prevention isn't just about avoiding harm but actively building a body that's resistant to the stresses of high-level sport.

Enhancing Athletic Performance

Rate of Force Development (RFD)

RFD is a critical metric in sports, referring to the speed at which an athlete can develop force. This is especially important in activities requiring explosive movements, such as sprinting or jumping. Year-round S&C programs that include Olympic lifts (e.g., cleans, snatches) have been shown to improve RFD, leading to better performance outcomes.

Neuromuscular Adaptations

These adaptations involve improvements in the brain's ability to communicate with muscles, resulting in faster and more coordinated movements. Continuous training ensures that these neuromuscular pathways are reinforced, leading to more efficient and powerful movements. This is particularly important in sports requiring quick changes of direction, such as soccer or basketball.

Example: In a study by DeWeese et al. (2015), athletes who engaged in year-round strength training, including explosive movements, demonstrated significantly higher RFD compared to those who only trained seasonally. This translated into better sprint times, higher jumps, and improved agility on the field.

The Role of Recovery

Active Recovery

Contrary to popular belief, recovery doesn't mean complete rest. Active recovery involves engaging in low-intensity activities that promote blood flow and help remove metabolic waste from muscles, facilitating quicker recovery. Examples include light cycling, swimming, or mobility exercises.

Overtraining Syndrome (OTS)

Overtraining occurs when athletes experience excessive training stress without adequate recovery, leading to decreased performance and possible long-term setbacks. Signs of overtraining include persistent fatigue, decreased motivation, and increased susceptibility to illness. A well-structured year-round S&C program incorporates periods of rest and recovery to prevent OTS while still allowing for continual improvement.

Kellmann (2010) emphasized that managing the balance between training stress and recovery is crucial for sustained performance. This balance is achieved through careful periodization, where phases of high-intensity training are followed by periods of reduced intensity, allowing the body to recover and adapt.

Mental Toughness and Discipline

Mental Toughness

This psychological trait refers to an athlete's ability to remain focused, resilient, and motivated in the face of challenges. Consistent, year-round training helps build this toughness by instilling habits of discipline and hard work. Athletes who train consistently are better equipped to handle the mental demands of competition, such as pressure, fatigue, and adversity.

Example: A study by Gucciardi et al. (2009) found that athletes who engaged in regular, structured training routines developed higher levels of mental toughness. This toughness is not just beneficial in sport but in life, as it fosters a mindset that is resilient, adaptable, and goal-oriented.

The Psychology of Consistency

The very act of adhering to a year-round training regimen can build confidence and self-efficacy, the belief in one's ability to succeed. This is because consistency in training leads to visible, measurable improvements in performance, reinforcing the athlete's commitment to their goals.

Real-World Application

Professional Sports

Year-round S&C isn't just for elite athletes—it applies to all levels of sport. Professional sports teams invest heavily in S&C programs that span the entire year, with periods dedicated to building base fitness, refining skills, and peaking for competition.

Youth Development

Even at the youth level, continuous training is critical. Young athletes are still developing their physical and mental attributes, making consistent S&C crucial for safe and effective development. Programs that incorporate periodized strength training, agility drills, and endurance work can help young athletes build a solid foundation that will support their long-term athletic aspirations.

Year-round strength and conditioning are vital for any athlete serious about reaching their full potential. The science behind continuous training supports its role in fostering continuous adaptation, preventing injuries, enhancing performance, and building mental toughness. By integrating strategic recovery and periodization, athletes can sustain progress, remain injury-free, and achieve peak performance when it matters most.

In a world where competition is fiercer than ever, the key takeaway is clear: there truly is "No Off-Season" in the pursuit of athletic excellence.

Dedicated to your success,

Sam

References:

DeWeese, B. H., Hornsby, W. G., Stone, M. H., & Stone, M. E. (2015). The training process: Planning for strength–power training in track and field. Part 2: Practical and applied aspects. Journal of Sport and Health Science, 4(4), 318-324.

Gucciardi, D. F., Gordon, S., & Dimmock, J. A. (2009). Advancing mental toughness research and theory using personal construct psychology. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 2(1), 54-72.

Issurin, V. B. (2008). Block periodization versus traditional training theory: A review. Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness, 48(1), 65-75.

Kellmann, M. (2010). Preventing overtraining in athletes in high-intensity sports and stress/recovery monitoring. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 20, 95-102.

Lauersen, J. B., Bertelsen, D. M., & Andersen, L. B. (2014). The effectiveness of exercise interventions to prevent sports injuries: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 48(11), 871-877.

Mujika, I., & Padilla, S. (2000). Detraining: Loss of training-induced physiological and performance adaptations. Part I. Sports Medicine, 30(2), 79-87.